| |

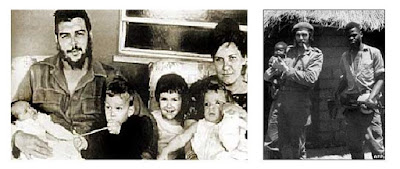

| Che Guevara: With his family, holding his baby (left and/or right?) |

I want to explore a fundamental question about the way we treat other human beings. It is a simple question, but one that ultimately, I think is critical for anyone with humanitarian pretensions, with a desire to ‘save the world’. It is this: is loving someone compatible with loving humanity? That is, can you love a single person while also loving people at large?

French philosopher Jacques Derrida, examining Aristotle’s Eudemian Ethics, once wrote:

It is not possible to love while one is simultaneously, at the same time (áma), the friend of numerous others (to de pollois áma einai phílon kai to phileîn kōlúei); the numerous ones, the numerous others – this means neither number nor multiplicity in general but too great a number, a certain determined excess of units. It is possible to love more than one person, Aristotle seems to concede; to love in number, but not too much so – not too many. It is not the number that is forbidden, nor the more than one, but the numerous, if not the crowd.

Depending on your interpretation, it is either impossible to love while one is in love with the crowd, or it is merely impossible to love the crowd – that is, humanity.

Let’s step back down from the heights of philosophy to some practical historical and contemporary examples. In the 1960s and 1970s in America, and arguably even today in many parts of the world, Che Guevara powerfully symbolized a love for humanity. A doctor and revolutionary who sacrificed his life for the cause of justice, he once famously said, “Let me say, at the cost of seeming ridiculous, that the true revolutionary is guided by sentiments of love.” For the moment, let’s ignore the problem of Guevara killing his enemies in guerrilla warfare (a problem common to any military struggle that either takes the enemy to lie outside of humanity, or envisions violence as part of the constitution of its own humanity). Let’s instead focus (perhaps ‘speculate’ is a better word) on the relationship between Guevara’s love for humanity and his love for his family – his father, mother, wife, and children. Of course, Guevara was quite often separated from his family while attempting to spark Marxist revolution across Latin America and Africa. His love was distant, as his personal letters reveal:

[To his parents] I have loved you very much, only I have not known how to express my affection. I am extremely rigid in my actions, and I think that sometimes you did not understand me.

[To his children, from Bolivia in 1966] Right now I want to tell you that I love you all very much and I remember you always, along with mama, although the younger ones I almost only know through photos, as they were very tiny when I left.

[To Dr. Aleida Coto Martínez of the Cuban Ministry of Education] Sometimes we revolutionaries are lonely. Even our children look on us as strangers. They see less of us than of the soldier on sentry duty, whom they call ‘uncle.’

[To a Spanish woman with the surname Guevara] I don’t think you and I are very closely related, but if you are capable of trembling with indignation each time that an injustice is committed in the world, we are comrades, and that is more important (my emphasis).

We see in Che’s personal letters the tensions between a revolutionary love for humanity and a love for his family. He spent so much time away that he and his children became something like strangers to each other. As much as he sent his love to them through his letters, his fatherly love was absent in everyday life. And, as he suggests to a Spanish Ms. Guevara, being a comrade was more important to him than being family. Guevara is not alone in history for dealing with this tension. Karl Marx, born middle class, became so dedicated to his philosophical work that his family fell into poverty, reliant on the earnings from his colleague Friedrich Engels’ father, a mill owner in Manchester.

I’m not interested in condemning these historical figures for neglecting their families, nor in attempting to argue that their relative neglect of their families somehow undermines the quality of their philosophy and work. But the contradiction between a love of one’s family and a love of Man asks serious questions about the meanings of ‘love’ and ‘humanism’. When we implicitly claim a ‘love of Man’ (literally: ‘philanthropy’), do we mean the same kind of ‘love’ that we would have for a parent, a child, or a partner? Is a humanist as obligated to a stranger on the street as she is to her mother? We could argue that she is merely asked to show a certain level of civic respect and responsibility to the stranger. But, as physician-anthropologist Didier Fassin has shown in his anthropology of humanitarian reason, even this common-sense logic can be torn apart in times of crisis or emergency. In what he calls the ‘inequality of life’, Fassin points out the underlying inequalities that separate not only aid workers from their beneficiaries, but Western aid workers from local aid workers. When, for example, imminent danger appears locally, international aid agencies usually evacuate their foreign personnel, leaving (in some cases) local staff to be killed. This kind of ‘lifeboat’ ethics – in which international aid workers are saved over local ones, or mothers are saved over strangers – contradicts the theory of humanism. Despite our liberal claims that human beings are born equal and have equal rights, we always privilege those closer to us in some way.

For those of you with interest or experience in international humanitarian work, this dilemma sounds familiar. I’ve spoken with many doctors who find it difficult to commit to global health as anything but an idealistic pursuit of young physicians. Love keeps them tied to friends and family in the United States, making a permanent and wholehearted commitment to global medical work (i.e. a globe of unmet medical need) nearly impossible. Programs like the Global Health Equity residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital allow medical residents to train both in Boston and abroad. But even if their employers are supportive, it can no doubt be hard to convince partners and even young children to move abroad for many months at a time. This no doubt in part explains the popularity of programs like Operation Smile, which – like military missions –swiftly jet in and out of areas where people do not have access to modern biomedical care. It’s little surprise that many of these types of organizations (Partners in Health excluded) emphasize intermittent specialized care over the establishment of national and regional primary care networks.

It’s tempting to expose humanism as a farcical or at least idealistic ideology, similar to human rights, the United Nations, and so forth. Great in theory, but doesn’t work in practice. But why doesn’t it work? Beyond the geopolitical decisions that undermine these institutions, there is a sense that these concepts require a sacrifice –a self-sacrifice* – that asks too much, that asks us to be superhuman or even nonhuman. It asks us to place our child’s needs equally next to that of a stranger’s, to forsake a family’s love for a love of humanity. Certain institutions – the US armed forces, for example – ask their recruits to adopt this philosophy of sacrifice, although usually only temporarily. Charismatic figures like Guevara sacrificed their love for and desire to be with their families for a love of humanity. Otherwise we can perhaps only think of machines as capable of responding equally to different individuals.

I am convinced that it is impossible to love a single person while also loving humanity. But perhaps more useful than this is to understand that such a contradiction is an eminently modern problem, in part created by webs of responsibility and dependence through the spindle of a globalized capitalist mode of production. Simply, we would find it difficult to think of ourselves as somehow responsible for the well being of distant others prior to establishing ourselves in relation to them, and in particular, in modes of domination characterized by colonialism, imperialism, class, and so forth. They are, as I frame them, also problems of a Western intellectual tradition that insists on the equality of Man (contrasting, for example, Indian caste or African networks of patronage). Even if we were to establish ourselves as dominant to others, it is primarily through the liberal concept of the rights of man born in liberal Enlightenment that we establish the basis for our practice of domination to contradict our ethics of care for others. Essentially, the idea that we should even be bothered by dominating others is a socially constructed idea.

I look forward to hearing your thoughts on whether you think one can be truly ‘humanitarian’ while being in love - if we are able to simultaneously love one and love all. Or does loving one merely expose the farce of ‘humanity’ and the impossibility of being humanitarian?

_______________________________________________________________

*We should be careful to recognize the culturally specific Judeo-Christian roots of the ideas of ‘sacrifice’ and ‘humanity’. For ‘sacrifice’, recall the Abraham and Isaac parable, in which Abraham’s faith in God is tested when he is asked to sacrifice his son Isaac for God. For ‘humanity’, we can turn to Auguste Comte’s ‘Religion of Humanity’. This notion of ‘humanity’ arose as secular rejection of Christianity, put Man in the place of God and calling for his worship. Despite rejecting the idea of God, ‘humanity’ as a concept is still molded within Christian philosophy.